COGNITIVE BIAS

Have you ever called your portfolio company ‘ambitious’?

Published date: 30 September 2024 | 5-Min Read

Companies are not people

Personification bias is deeply embedded in human cognition. It can be traced back to ancient times when myths and stories were used to explain natural phenomena by attributing human qualities to gods or forces of nature.

For example, the ancient Greeks believed that Poseidon’s anger caused storms and earthquakes. This tendency to humanize inanimate and explain events through personal characteristics persists today, even in modern decision-making, such as in investing.

Dunning-Kruger Effect: Confidence vs. Skill in Investment Decisions

The Knowledge/Skill vs. Confidence graph, often used to illustrate the Dunning-Kruger effect, shows how individuals with limited experience tend to overestimate their abilities, while those with deeper expertise may initially underestimate their skills.

Early on, confidence is high despite a lack of knowledge, leading to overconfidence in one’s abilities. As individuals gain more experience and realize the complexity of a subject, confidence dips before eventually rising again, this time more aligned with their true level of skill.

For venture capitalists, this dynamic mirrors the illusion of skill, where early success can lead to overconfidence in one’s ability to pick winners, disregarding the role of luck and external factors.

As investors gain experience, they begin to understand that success is influenced by timing, market conditions, and other forces beyond their control. Recognizing these complexities encourages a more balanced, humble approach to decision-making, rather than over-relying on past successes or star founders.

Another more recent (in comparison to the Ancient Greeks Timeline) example of personification bias is Microsoft’s Clippy, the animated paperclip assistant introduced in the late 1990s.

Clippy was designed to help users navigate Microsoft Office, but its overly humanized personality often led users to ascribe emotional traits to it. People saw Clippy as annoying, intrusive, or overly eager, even though it was just a program following a set of algorithms.

This anthropomorphism—the act of ascribing human traits to non-human entities—highlights how easily we fall into personification bias, even with technology.

Similarly, investors often assign human traits like “ambition” or “resilience” to companies based on their narratives, even when the underlying data tells a different story.

The emotional power of a narrative

Founders pitch their companies with compelling narratives of disruption, growth, and vision, painting their startups as forces of change. However, when investors treat companies like people, they are prone to a narrative fallacy, where the emotional power of the company’s story overshadows objective data and analysis. Investors may fall in love with the story of the struggling underdog or the visionary founder, leading them to make emotionally driven decisions.

Founders often become synonymous with their companies. A charismatic, energetic, or visionary leader can cause investors to believe the company itself has those same qualities.

This over-reliance on the „founder as company“ narrative can lead to overconfidence in the business’s potential, even when the financial fundamentals are lacking. The emotional attachment to the founder’s persona can blind investors to operational issues, market realities, or competitive risks that would otherwise warrant more cautious evaluation.

Does a disruptive founder equal a disruptive company?

In its early years, Uber was often seen as an aggressive disruptor, driven by the personality of its founder, Travis Kalanick. Investors projected Kalanick’s bold, relentless approach onto the company itself, believing that Uber’s success was inevitable due to its fierce approach to market domination.

However, Uber’s aggressive culture, which mirrored Kalanick’s leadership style, eventually led to numerous scandals and operational challenges. As Uber faced public scrutiny and legal battles, investors were forced to reassess whether Kalanick’s personality was an asset or a liability, highlighting the risks of conflating the founder’s persona with the company’s long-term prospects.

Or

Faraday Future, an electric vehicle (EV) startup, initially attracted significant investment by positioning itself as a bold competitor to Tesla. Its founder, Jia Yueting, cultivated a visionary persona, which led investors to believe the company shared his disruptive vision.

However, despite the excitement around its potential, Faraday Future repeatedly missed production deadlines and faced serious financial challenges. Investors who had personified the company as “ambitious” and “disruptive” found themselves overlooking critical issues like poor management and operational inefficiencies. This is another clear example of how personification bias can overshadow essential business fundamentals.

Visionary founders don’t guarantee success

Jeff Bezos is frequently personified as the visionary behind Amazon’s rise to dominance in e-commerce. His relentless focus on customer experience and innovation has led to tremendous growth.

However, Amazon has faced significant challenges, such as controversies over labor practices and failed ventures like Amazon Fire Phone. These instances illustrate that even a highly regarded founder cannot ensure success in every initiative.

The dangers of doubling down

One of the most significant risks of personification bias is that it can lead investors to double down on underperforming companies. When investors emotionally connect to a company or its founder’s narrative, they are more likely to continue funding it even when it is struggling.

This can be especially dangerous in venture capital, where the pressure to back “winners” can make investors hold on to poor-performing portfolio companies longer than they should.

Investors who view a company as “resilient” or “tenacious” may continue to support it in the hopes that it will eventually overcome its challenges. However, this kind of emotional attachment can cloud judgment, leading to several key risks:

1. Overcommitting to failing ventures:

By allowing personification bias to drive decisions, investors may pour more capital into a company that lacks the fundamentals to succeed. This can result in wasted resources that could have been better allocated to other, more promising ventures.

2. Overlooking warning signs:

Emotional attachment to a narrative can cause investors to ignore red flags, such as consistently missed milestones, cash flow problems, or shifting market conditions. The belief that the company will “figure it out” often delays crucial decisions about whether to pivot or divest.

3. Missed opportunities:

By doubling down on an underperforming portfolio company, investors may overlook better opportunities elsewhere. The emotional attachment to a struggling company can prevent investors from reallocating their capital to startups with stronger fundamentals and clearer growth potential.

4. Loyalty to underperforming companies:

Investors may stick with a company longer than they should, not because of strong fundamentals but due to the belief that the company will „persevere“ or „fight through“ tough times. This can lead to wasted capital on businesses that are unlikely to turn a profit

Personifying market trends

Personification bias doesn’t just apply to companies or founders; it also emerges in how investors talk about and interpret broader market movements. Phrases like “the market is punishing” or “the market is excited” are common as if the market itself has intentions or emotions. This emotional framing can lead investors to make rash decisions based on perceived market „moods,“ rather than relying on objective analysis.

For instance, during the 2015 oil price crash, many investors reacted to the sudden downturn by personifying the market as „fearful“ or „panicking.“ Instead of focusing on the underlying causes—such as global oversupply and geopolitical factors—investors attributed human-like emotions to market behavior.

This led some to exit positions prematurely out of fear, while others held on too long, expecting a „recovery“ as though the market would behave rationally, like a human entity. By interpreting market dynamics emotionally, these investors missed critical opportunities for data-driven decision-making, ultimately leading to suboptimal outcomes.

In venture capital, the same dynamic can occur. Viewing the market as „favoring“ or „punishing“ certain types of companies can cause investors to react emotionally, rather than relying on rigorous analysis of market conditions. Recognizing and avoiding this tendency to personify market trends is essential for making well-informed, rational investment decisions.

How to avoid personification bias

To avoid the pitfalls of personification bias, VC fund managers should focus on creating a disciplined, data-driven approach to investing. Here are several key strategies to help mitigate this bias:

1. Focus on data, not stories:

While a compelling narrative can be persuasive, always ensure that your investment decisions are grounded in data. Evaluate companies based on their financial performance, market dynamics, and execution, not just the story they tell or the charisma of their founder.

2. Separate the founder from the company:

A charismatic or visionary founder can be an asset, but it’s important to distinguish between the individual and the business itself. The company’s long-term success must be based on its strategy, execution, and market position—not the personality of its leader.

3. Regularly reassess your portfolio:

Periodically review each company in your portfolio with fresh eyes, focusing on measurable progress and business fundamentals. Reassess your investment thesis and ensure that any decisions to double down or exit are based on objective analysis, not emotional attachment to a narrative.

4. Apply a Decision Analysis Framework to Evaluate Your Companies:

Ulu Ventures, a prominent venture capital firm, applies a decision analysis framework to evaluate early-stage investments with more precision.

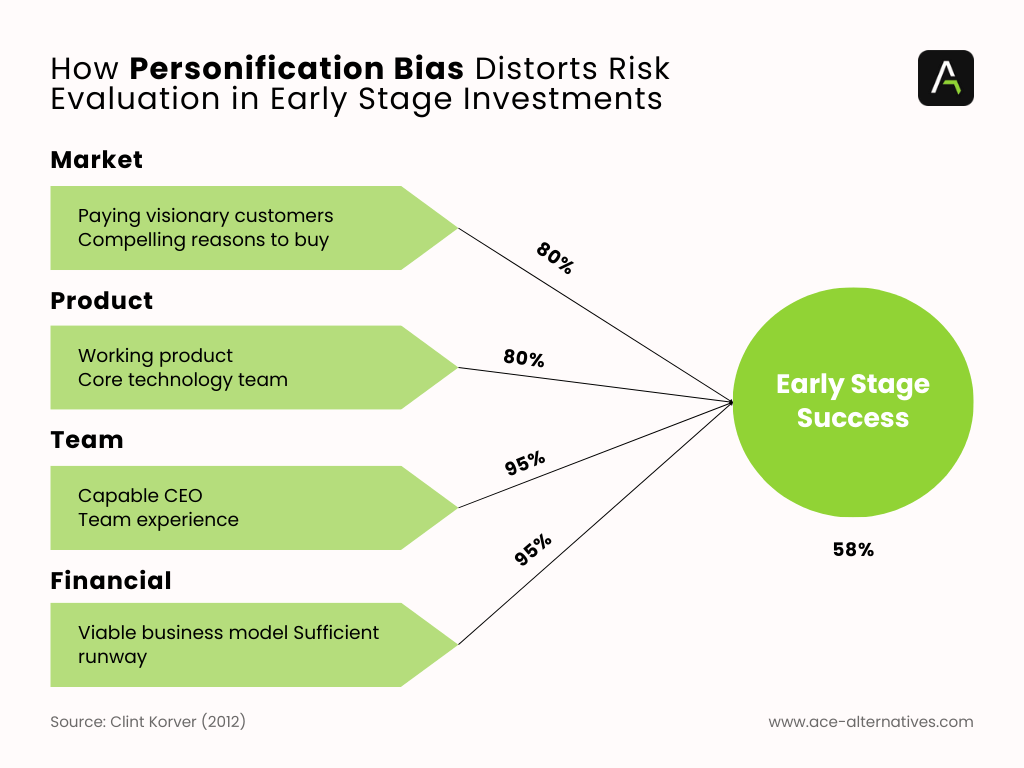

How Personification Bias Distorts Risk Evaluation in Early Stage Investmetns

As shown in the diagram, their process breaks down key risk categories into market, product, team, and financial factors, each assigned a probability reflecting the likelihood of success.

For instance, in evaluating a company like Inkling, Ulu Ventures estimated an 80% chance of market success, based on the startup’s ability to attract visionary customers with compelling reasons to buy. Similar probability estimates—80%, 95%, and 95%—were assigned to the product, team, and financial categories, considering factors such as the working proof of concept, the CEO’s experience, and strong financial backing.

By multiplying these probabilities, they calculated an overall 58% chance of early-stage success. This framework allows them to simplify complex decisions, directing focus on key risks and opportunities while acknowledging the uncertainty inherent in early-stage ventures.

Through this structured approach, Ulu Ventures reduces the cognitive biases that can distort investment decisions, ensuring a clearer path to high-quality outcomes. For the full article read Applying Decision Analysis to Venture Investing by Clint Korver

Overcoming personification bias

Personification bias is a subtle but powerful cognitive force that can significantly shape investment decision-making in venture capital. It occurs when investors project human characteristics onto companies or markets, leading to skewed judgments and emotional attachments.

However, by recognizing this bias and adopting strategies to counteract it, investors can make more rational, informed decisions and achieve better results.

ACE Alternatives acknowledges the potential impact of personification bias and aims to empower fund managers with advanced tools and real-time insights that minimize the influence of emotional narratives.

By integrating objective data-driven methodologies into investment processes, this collaboration aims to foster a more disciplined approach to decision-making throughout the fund’s lifecycle.

Source:

Rolf Dobelli, “The Art of Thinking Clearly” (2013)

About ACE Alternatives

ACE Alternatives, a leader in managed services for the Alternative Assets sector, specializes in venture capital, private equity, fund of funds, private real estate, and more. Leveraging tech-driven processes and extensive industry experience, ACE offers tailored solutions for fund administration, compliance and regulatory, tax and accounting, investor onboarding and ESG needs.

Our vision is to redefine fund management standards with data-driven processes, combining advanced technology with deep industry knowledge. We are committed to demystifying complex fund operations, promoting transparency, and achieving sustained growth across the fund lifecycle.